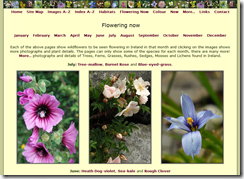

Dandelions are found all over Ireland and are one of our most widespread and successful wildflowers. They grow almost anywhere; their unmistakable yellow flowers, their downy seed-heads and their familiar toothed leaves greet us from hedgerow and pasture, meadow and parkland, roadside verge and garden. The plants are at their most prolific in early spring and summer, but continue to flower and seed until well into the autumn.

Dandelions are found all over Ireland and are one of our most widespread and successful wildflowers. They grow almost anywhere; their unmistakable yellow flowers, their downy seed-heads and their familiar toothed leaves greet us from hedgerow and pasture, meadow and parkland, roadside verge and garden. The plants are at their most prolific in early spring and summer, but continue to flower and seed until well into the autumn.

Dandelions take their English name from the French “Dent-de-leon”, or Lion’s teeth, referring to the toothed edges of the leaves. The flower itself is linked with St Briget here in Ireland, and is called by some “the little flame of God” or “the flower of Saint Bride”.

Many insects rely on the dandelion as a food source for themselves and for their larvae. Several of our native butterflies and moths lay their eggs on dandelion leaves and the bright yellow flowers, with their generous stores of nectar, are a magnet to pollinating insects like bees and hoverflies. The seed heads are also a valuable food source for seed eating birds like the goldfinch.

Dandelions are among the first colonisers of waste ground. Along with other colonising plants they help to stabilise soil conditions, attract other species into the area and pave the way for the development of a rich, stable ecosystem.

One of the aspects that makes the dandelion such an effective coloniser is its method of dispersal. The downy parasol of the seed-head is made up of myriad seeds, each suspended on an individual gossamer parachute ready to be carried away by the slightest breeze. As children, most of us have unwittingly helped the dandelion in its colonisation by collecting and blowing the seed heads.

The long central "tap root" of the dandelion is particularly effective at drawing nutrients from deep in the soil. Its leaves are packed with these valuable nutrients and, when the plant dies (or is pulled up by the gardener and added to the compost heap), those nutrients are released back into the surface layers of the soil and made available to other plants.

It may be an alien concept to most gardeners, but actually allowing dandelions to grow in the garden and harvesting the leaves as compost material or mulch is an excellent way of recycling nutrients in the soil and keeping the garden fertile.

Success as a species is the very reason that the dandelion is so reviled. Its ability to colonise new areas quickly, its incredibly prolific nature, and its ability to out-compete cultivated plants do little to endear it to gardeners and crop-growers. Many people see the dandelion as a pest to be completely eradicated, but luckily the plant is too resilient to succumb to our repeated attempts at botanical genocide.

The first part of the scientific name Taraxacum is derived from the Greek words Taraxos, meaning disorder, and akos, meaning remedy. In the past the curative power of dandelions has been advocated as treatment for a variety of ailments including liver complaints, upset stomach, bilious disorders, dropsy, dizziness, gall stones, jaundice, haemorrhoids and warts.

Other uses of the plant are also well documented. Young leaves make an excellent salad and can also be used as a green vegetable. Dried leaves are a common ingredient in many digestive and herbal drinks and are used for making herb-beer, including a dandelion stout. The flowers can be made into dandelion wine, which has a reputation as an excellent tonic, and the dried roots, when roasted and ground, make an effective substitute for coffee.

The dandelion is far from the useless weed that many people dismiss it for. In fact it is an underrated, successful little plant that plays an important role in nature. It also has many useful properties that people have exploited through the ages and continue to make use of to this day.

1 comment

Sandro Cafolla

They are great as rabbit food, so many fields full of Dandelion and so few rabbits bred for the table.