A trip to the coast practically guarantees a close encounter with the herring gull. This is the ubiquitous “seagull”: its mewling cries synonymous with the seaside, its strong profile and bold manner familiar to us all.

A trip to the coast practically guarantees a close encounter with the herring gull. This is the ubiquitous “seagull”: its mewling cries synonymous with the seaside, its strong profile and bold manner familiar to us all.

These large, noisy gulls are common around our coasts all year ‘round, and often venture inland to congregate around rubbish tips, ploughed fields and inland reservoirs or lakes, particularly during the winter months.

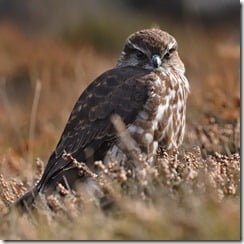

The herring gull’s pale grey back makes it easy to distinguish the species from the otherwise similar black-backed gulls, while the red spot on the underside of the bill, its larger size and more menacing appearance set it apart from the common gull.

Herring gulls usually nest in large colonies on coastal cliffs, offshore islands or sand dunes, although other nesting sites, such as flat roofs in seaside towns and the occasional chimney stack are not uncommon. The nest is typically built out of grass, seaweed and bits of jetsam collected from the strand-line by both parents. Two to three pale green eggs are laid from April to May and both parents incubate the eggs for some 28 to 33 days.

Young herring gulls are able to leave the nest a few days after hatching, but stay nearby, within their parents’ territory, until they fledge some six weeks later. Those that stray too far quickly become a meal for opportunistic adults in neighbouring nests.

In common with other gulls both parents feed the young with a remarkable diversity of food obtained primarily by scavenging. Herring gulls eat practically anything, with a typical diet consisting of various invertebrates, fish, carrion, small birds, eggs and refuse. These are the gulls that most frequently follow fishing vessels in the hope of securing a tasty morsel, and that seem to appear from nowhere behind the farmer’s plough to gorge themselves on invertebrates exposed by the freshly turned earth.

In common with other gulls both parents feed the young with a remarkable diversity of food obtained primarily by scavenging. Herring gulls eat practically anything, with a typical diet consisting of various invertebrates, fish, carrion, small birds, eggs and refuse. These are the gulls that most frequently follow fishing vessels in the hope of securing a tasty morsel, and that seem to appear from nowhere behind the farmer’s plough to gorge themselves on invertebrates exposed by the freshly turned earth.

Herring gulls are surprisingly intelligent birds, and can find ingenious ways to exploit otherwise unavailable food sources. Adult birds, for example, have learned to drop hard-shelled molluscs, like mussels, onto rocks to break them open and expose the contents. The gulls judge the height of the drop to perfection, so that the fall is just enough to break open the hard shell, but not enough to scatter the edible contents.

Populations all over northern Europe boomed earlier this century as this opportunistic bird took advantage of man’s wasteful nature. Our burgeoning refuse sites and overflowing sewage systems provided a wealth of scavenging opportunities for the gulls, while our buildings offered perfectly secure undisturbed nesting sites. Since the 1970’s however herring gull populations have fallen sharply, and the species is considered to be in decline. The UK population is thought to have fallen by up to 40% in the last thirty years, prompting the RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) to add this most familiar of gulls to its “Amber” list of species that are of medium conservation concern.

The opportunistic nature of herring gulls and their fearless, sometimes aggressive demeanour, leads to them being much maligned wherever people and gulls coexist. They tend to be regarded as pests because of the very trait that has helped to make them such successful birds – namely their ability to exploit our wastefulness. In many places they are persecuted because of it.

The opportunistic nature of herring gulls and their fearless, sometimes aggressive demeanour, leads to them being much maligned wherever people and gulls coexist. They tend to be regarded as pests because of the very trait that has helped to make them such successful birds – namely their ability to exploit our wastefulness. In many places they are persecuted because of it.

All of which begs the question who is the villain here? The gulls are merely exploiting our wasteful nature, and happen to do it very successfully. People who see herring gulls as pests should perhaps stop blaming the birds and look a little closer to home for the root cause of the problem!

1 comment